Democratised Modular Controller Production

Award-winning submission for Device Prototyping And Production Summer School

PDF Version: Democratised Modular Controller Production

About the Summer School

The project was submitted to the pro² network+ device prototyping and production summer school; this three-day event included presentations, demos, hands-on lab-based tutorials, panels, and discussions on building refined and robust prototypes. I attended the summer school on a sponsored place for the initial project proposal. During the summer school, I gained professional insight into PCB design and manufacture, component selection and sourcing, and designing for manufacturing. I had hands-on experience with surface mount assembly, reliable firmware, and testing through solder:bit. Many great projects were presented over the course of the summer school, such as Wakayima and Print and Place Isotyping Board, with prizes given to those that showed the greatest potential for impact. My project was selected for one of the three £1000 awards by the pro² network+, which will be used to fund the studies and ensure end-users can receive prototypes for free.

The Proposal

This research aims to democratise accessible controller production through a modular leverless controller that users can design and modify with low technical knowledge requirements; this should benefit individuals with degenerative illnesses.

Introduction

The World Health Organization identified the current barriers to assistive technology for people with a disability, including high costs, procurement challenges, and inadequate product range[22]; democratising accessible hardware production would reduce or mitigate these barriers[12] and enable the viable development of devices tailored to individual users. Due to the lack of democratisation in accessible controller production[9], gamers with disabilities face financial barriers to entry[4], which are exacerbated by the cost of living for people with disabilities[20] and poor consumer choice[4].

Baltzar et al.[5] found that custom controllers were one of the most used and needed products for disabled gamers but were considered too expensive or hard to source by those surveyed; further research[6, 23] has found that many mainstream games can be inaccessible to gamers with disabilities due to control mechanisms and an inability to input the necessary commands due to current controller design. Currently, accessible controllers are too general for most individuals[4], so gamers with disabilities often rely on modifications from charities, such as The Controller Project; disabled gamers will be better served and be able to take ownership of controller development through the democratisation of accessible controller production[12].

Currently, accessible physical controllers cannot be modified specifically for user needs, so the community has taken a DIY approach[13]. Accessible controller breakthroughs[9] rely on customisable virtual interfaces[15], which are not suitable for tournament play or portability or are designed for specific individuals and contexts, limiting the number of users who can benefit from the products. Larreina-Morales[14] identified that while customisation is key to creating an accessible experience, many modern controllers lack full customizability. Stoner[18] discussed the need for evolving customisable accessible hardware for individuals with progressive illnesses and accessible hardware with small form factors for portability, which highlights issues with current accessibility controllers.

Egliston[10] identified that disabled gamers are reliant on third-party developers for the creation of specialised devices, with Dalgleish[8] highlighting that as games rapidly evolve, the interaction demands on gamers with disabilities become unfeasible; this results in an ecosystem with a growing number of inaccessible games and a user reliance on third-parties rather than the game developers themselves.

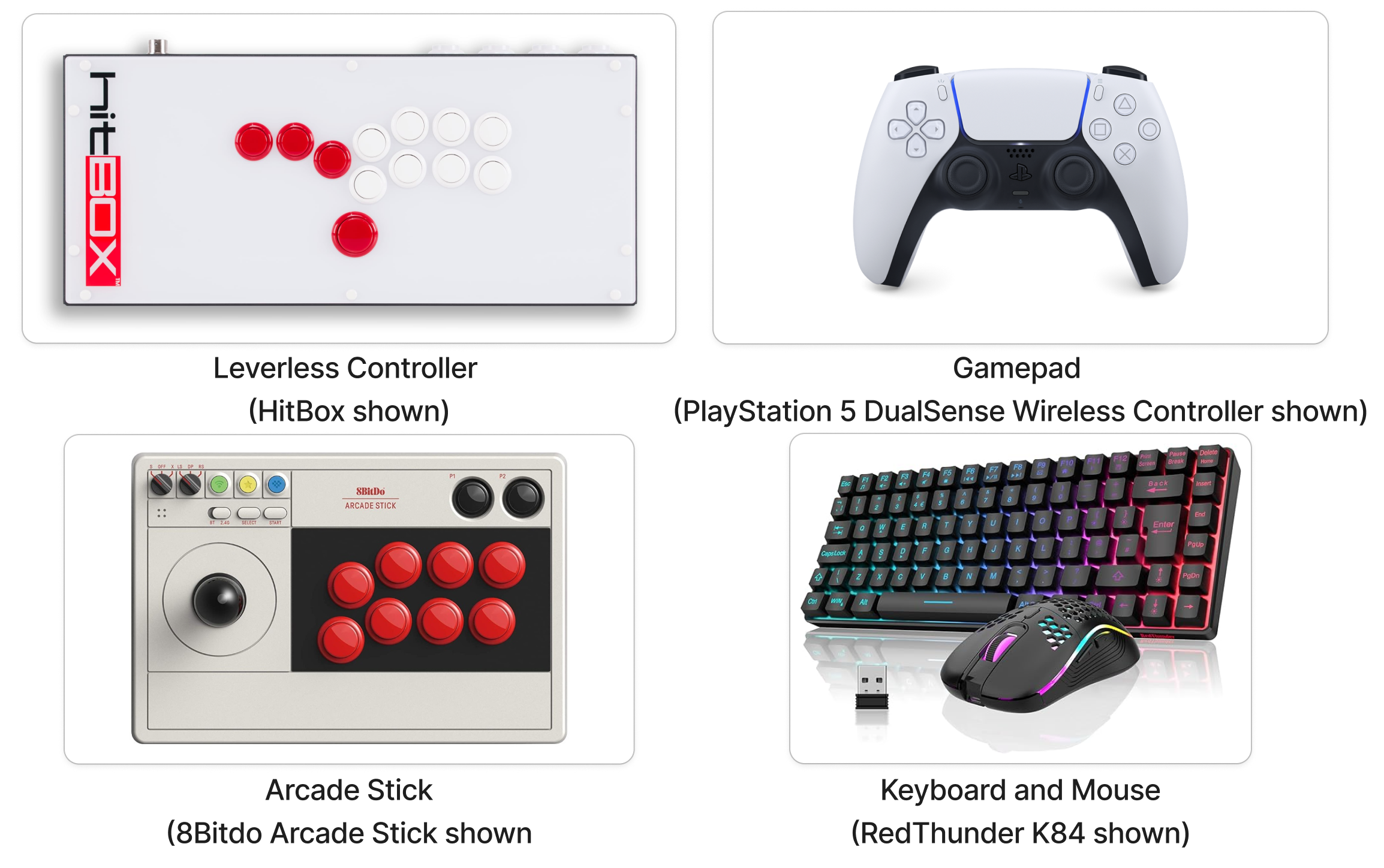

The fighting game community has a wide range of controller types and preferences utilised by users[11]; examples can be seen in Figure 1. Due to the variance in user preferences, developers of consumer controllers for fighting games have begun creating modular systems that enable user customisation; however, these controllers rely on preset modules that users cannot fine-tune. DIY projects, such as Open Ultra Arcade, simplify user creation of controllers but require knowledge of CAD and electrical engineering for fine-tuning as they only provide preset controllers and module templates rather than a simplified design suite.

Figure 1: Fighting Game Community Controllers

The need for evolving customisable accessible hardware for individuals with progressive illnesses[18] has been reiterated by the charity AbleGamers[1]. Prior research into game controller design for individuals with degenerative illnesses[7] identified the potential design challenges within this domain but viewed symptoms of the illnesses as discrete, assuming users either had or didn’t have the symptom; currently, there is no research within game controller design that views degenerative illness symptoms as continuous and evolving, which is true to their nature.

Related Work

While there are currently no evolving controllers, the Xbox Adaptive Controller is state-of-the-art for adaptive controllers[16]; the Xbox Adaptive Controller serves as a hub for accessible input devices, with many gamers with disabilities using the hub within their gaming setup[21]. Anabire’s case study on the Xbox Adaptive Controller[3] found that the controller was aimed towards gamers with limited mobility issues and was designed to be fully customisable; however, the controller relies on third-party modules to meet user needs and may have a financial barrier to entry for those that need the controller most[18]. The Xbox Adaptive Controller can be adapted over time for individuals with degenerative disorders; however, many of the available add-ons for the controller are too generalised[4]. The Xbox Adaptive Controller also assumes advanced needs and may not be suitable for individuals who are only just beginning to experience symptoms of degenerative disorders.

Controllers Maggiorini et al.’s One-Handed Controller[15] is a customisable virtual adaptive controller built for individuals with upper limb disabilities; the controller builds upon commercial devices designed for gamers with one hand, such as the ASCII Grip[7]. The controller itself has an analogue joystick and a touchscreen display that enables users to customise a virtual controller interface. Within the research paper for the controller, it was identified that the controller could be uncomfortable to use, is less suited for gamers with physical disabilities than a general controller, and often users were unhappy with the configuration options[15]. Maggiorini et al.[15] found that users saw potential in highly customisable devices for gamers with disabilities, but the implementation required refactoring.

Video-game-related studies often focus on game design and usability rather than the controllers and physical interfaces[2]; however, research that focuses on video game controllers has found that mapping, which users deem to be natural, is key to user acceptance[2]. Comfort and performance are important to user acceptance of a controller[2], but these factors are correlated to the mapping of a controller[17]. Allowing individuals with degenerative illnesses to evolve their controller mappings as their illnesses progress would enhance their acceptance of controllers, which should reduce the barrier to entry for these gamers.

Gaming peripheral companies have created modular hot-swappable controllers for able gamers, such as the Razer Naga Trinity, as seen in Figure 2; however, through research for this project, 3D-printable and console-compatible hotswap solutions could not be identified.

Figure 2: Razer Naga Trinity

Imagined or Existing Prototype Sketches/Drawing/Photos

The prototype will utilise a leverless controller interface style, as seen in Figure 1, for simplicity of design. The prototype aims to enable hot-swappable modules for a leverless controller that users can plug and play without the need for remapping. The key design challenges are developing a way for mapping to be memorised in modules, designing a standardised method for hot-swapping modules, and producing an easy-to-use tool for creating modules. The design objective can be summarised as follows:

- Develop a modular leverless controller

- Enable hot-swappable and plug-and-play modules

- Enable easy remapping for the controller

- Create methods for generating new modules

To achieve the design objectives, the prototype should be built upon the RP-2040 microcontroller to enable GP-2040 configuration; GP-2040 is a multi-platform compatible, customisable firmware for game controllers using RP-2040. 3D model designs should be generated parametrically, with a simple user interface for modification of the parameters, to enable users with lower technical ability to generate modules. A singular base should be developed, with the majority of circuitry contained within it; this enables users to only need to modify the modules rather than the entire controller. Kailh switches enable buttons to be hot-swappable, too, with little know-how, enhancing the modularity of the controller.

Design Sketches

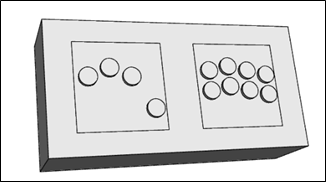

GP-2040’s documentation provides PCB pin-outs for most RP-2040 boards, so a new PCB design is required for the prototype. An initial parametric model has been created in CADQuery, as seen in Figure 3, but requires refinements, including hollowing the objects, adding a USB port, and enabling users to access the internal area of the objects. The model in Figure 3 was built parametrically, enabling all buttons to be manipulated using variables; currently, buttons are modified through variables for button size, spacing, slope of buttons, and position of the left module’s thumb button.

Figure 3: CADQuery Model for Prototype Controller

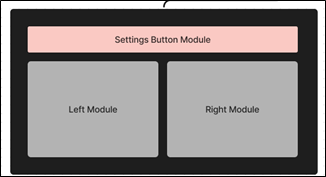

The next iteration of the prototype will include a module for the GP-2040 settings buttons, as seen in Figure 4; improvements that are planned for the next iteration also include a USB port and hollowed interiors. Multiple iterations will be made for tolerance testing of the next model to identify the required wall thickness.

Figure 4: Module Layout for Prototype Controller with Settings

Hot-swap Methods

Enabling hot-swappable and plug-and-play modules for the modular controller is a key design focal point; this prevents users from having to remap controllers whenever a module is changed. Currently, the prototype design has two proposed methods: a pin-based and an RFID-based method.

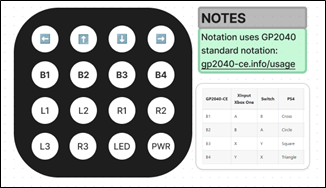

The pin-based method is simplistic in design, with modules communicating with the base controller via electrical pins that correlate to GP-2040 mapping, as shown in Figure 5; this method may wear over time and is reliant on either magnetic connection and pogo pins, akin to the Razer Naga Trinity, or a large pin and leg connection, as used by keyboard switches.

Figure 5: Proposed Hotswap Pin Notation

The RFID method would enable modules to be quickly swapped with mapping stored in an RFID chip; however, this would rely on modification of the GP-2040 firmware per module.

Further Design Notes

To simplify module creation, a board that sits each switch could be created; this should be parametrically modifiable. The board for switches would enable users to easily swap switches based on user preference and allow for wiring to be simplified by embedding it into a singular system.

The prototype could be further enhanced to enable users with low technical skills to develop modules by implementing a universal design method; this could enable modules to ‘snap’ together, similar to Lego, with no wiring, soldering, or screws required.

Currently, the modular controller only implements a leverless design, relying on buttons and switches to control all inputs. The creation of modules that incorporate joysticks, sliders, and other inputs would enhance the accessibility of the controller while enhancing user choice.

Responsible Innovation

While environmental sustainability is not the focal point of this prototype, it is a byproduct of the design. Research into controls for gamers with disabilities results in bespoke controllers[15], but these controllers need to be completely replaced when changes are required; modularity within controller design enables users to replace only the parts of their controller that require modification, reducing waste. Modularity could also reduce waste for non-disabled gamers; for example, if an individual wanted a leverless controller and arcade stick, as seen in Figure 1, they could simply buy or create a joystick and a leverless movement input module for their controller instead of having to buy two controllers. Modularity also greatly increases user freedom and customisation as the number of layouts l available to a user with n modules can be calculated using the below equation, resulting in exponentially less waste and resource consumption as users opt for modules over new controllers.

\[l= n^2+n\]The research will aim to follow the responsible innovation process[19] by identifying potentially negative impacts on users and barriers to adoption and attempting to mitigate these. The design of modules for the controller is a potential barrier to adoption, and due to this, it could be identified as an area for harmful monetisation by third parties; to avoid this barrier of adoption, open-source methods that enable users to develop modules themselves will be created. The key societal benefit of the prototype is that it provides gamers with degenerative disabilities, which are currently overlooked within controller development, with a platform that enables the development and design of controllers that can evolve over time. The prototype will begin to democratise accessible controller design by providing ownership of accessible controller production to gamers.

Author Bio/Experiences

This research is part of a larger PhD project that aims to create tools to assist in the design and development of accessible user-tailored controllers. The research was inspired by the impact that accessible controllers can have on children with disabilities, especially in regard to social isolation; this is an intersect of two areas I have a lot of time and enjoyment for, as I have a background in secondary school and college teaching and actively play video games.

My key skills and expertise are within HCI and UX design, Python programming, and Interactive AI. My experience in hardware and electrical engineering is primarily through my BSc in computer science, but it is an area I want to explore further through my research. Since starting my PhD, I have begun to explore CAD design through CADQuery and KiCad but have not yet created any physical interfaces; however, I will be creating physical prototypes prior to summer school. I have knowledge of C/C++ and prior experience with Arduino and RP-2040 microcontrollers.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Anne Roudaut for suggesting the summer school for this research and supervising my PhD project alongside Paul Marshall and Oussama Metatla, and to the UKRI and the University of Bristol for funding my research.

References

[1] AbleGamers, ‘Gaming with a progressive disease’, AbleGamers. Aug 2022.

[2] S. Akyaman and E. C. Alppay, ‘A Critical Review of Video Game Controller Designs’, in Game + Design Education, 2021, pp. 311–323.

[3] D. A. Anabire, ‘User-Centered and Inclusive Design toward Social Justice: The Case Study of the Xbox Adaptive Controller, Apple Siri, and SteadyMouse’, 2022.

[4] J. Archer, ‘“They don’t care”: Inside the triumphs and failures of accessible gaming hardware’, Rock Paper Shotgun. Rock Paper Shotgun, Sep-2023.

[5] P. Baltzar, L. Hassan, and M. Turunen, ‘Assistive technology in gaming: A survey of gamers with disabilities’, 04 2023.

[6] J. Beeston, C. Power, P. Cairns, and M. Barlet, ‘Accessible Player Experiences (APX): The Players’, in Computers Helping People with Special Needs, 2018, pp. 245–253.

[7] K. Bogdanov, ‘Designing a Game Controller for Players with Motor Impairments: An Aim at Increasing Accessibility in Playful Experiences’, Dissertation, 2023.

[8] M. Dalgleish, ‘“there are no universal interfaces”: How asymmetrical roles and asymmetrical controllers can increase access diversity’, GAME. Ludica, Dec-2018.

[9] M. Dalgleish, ‘Who Can Play? Rethinking Video Game Controllers and Accessibility’, in Disability and Video Games: Practices of En/Disabling Modes of Digital Gaming, M. Spöhrer and B. Ochsner, Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2024, pp. 43–71.

[10] B. Egliston, ‘It’s designers who can make gaming more accessible for people living with disabilities’, The Conversation, The Conversation US, 2019.

[11] T. Harper, The culture of digital fighting games: Performance and practice. 11 2013, pp. 1–157.

[12] S. Hodges, ‘Democratizing the Production of Interactive Hardware’, in Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, Virtual Event, USA, 2020, pp. 5–6.

[13] A. Hurst and J. Tobias, ‘Empowering individuals with do-it-yourself assistive technology’, in The Proceedings of the 13th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Dundee, Scotland, UK, 2011, pp. 11–18.

[14] M. E. Larreina-Morales, ‘How Accessible is This Video Game? An Analysis Tool in Two Steps’, Games and Culture, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 75–93, 2024.

[15] D. Maggiorini, M. Granato, L. A. Ripamonti, M. Marras, and D. Gadia, ‘Evolution of Game Controllers: Toward the Support of Gamers with Physical Disabilities’, in Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications, 2019, pp. 66–89.

[16] S. C. Murphy and A. Lefloïc-Lebel, ‘Controllers’, in The Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies, Routledge, 2023, pp. 17–24.

[17] R. Rogers, N. Bowman, and M. B. Oliver, ‘It’s not the model that doesn’t fit, it’s the controller! The role of cognitive skills in understanding the links between natural mapping, performance, and enjoyment of console video games’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 49, pp. 588–596, 08 2015.

[18] G. Stoner, ‘How accessible hardware bridges the gap between individuals and options’, IGN. IGN, Feb-2024.

[19] UKRI, ‘Responsible Innovation’, UKRI. Jan-2024.

[20] L. Veruete-McKay, L. Schuelke, C. Davy, and C. Moss, ‘Disability Price Tag 2023 technical report ‘, SCOPE, 2023.

[21] J. Wentzel, S. Junuzovic, J. Devine, J. Porter, and M. Mott, ‘Understanding How People with Limited Mobility Use Multi-Modal Input’, in Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2022.

[22] World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund, Global report on assistive technology. World Health Organization, 2022, pp. xiii, 125 p.

[23] B. Yuan, E. Folmer, and F. C. Harris, ‘Game accessibility: a survey’, Universal Access in the Information Society, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 81–100, Mar. 2011. \

Appendix

The Jupyter Notebook used to generate the model seen in Figure 3 can be found at Pro2CadQueryModel.ipynb

Future of the Study

This study will be developed incrementally through different projects. VirtualLeverless will develop a customisable virtual controller, to enable the collection of user controller layout preferences. ControllerForge will use the data collected by VirtualLeverless to generate 3D-printable controllers that are tailored to user needs. GeneRoute enable for 3D-printed circuitry, through optimising conductive filament wiring within ControllerForge. The proposed research project will build on ControllerForge to enable the modular design and creation of user-tailored controllers.